“You can’t use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have. Sadly, too often creativity is smothered rather than nurtured. There has to be a climate in which new ways of thinking, perceiving, and questioning are encouraged.” —Maya Angelou

Imagine this:

You are in a meeting with your team, and the boss is explaining a proposed solution for a major problem on the horizon. As you scan the room, you notice most of your team is making the same face of doubt. You’ve been thinking about this problem yourself and have an idea for how to address it, but now you wonder if it’s acceptable for you to share.

Your train of thought is interrupted when the boss announces: “Everyone thinks this is the right plan, correct?” Everyone quickly nods in agreement. One person even states why he thinks this plan will be a success.

After the meeting, you don’t want to gossip with your co-workers that you think this is a terrible idea, but you wonder why nobody decided to speak up when they had the chance. At this point, the best you can do is complete the work assigned and wipe your hands of it. Having done your part, you sit back and wait for the plan to fail.

What is Psychological Safety?

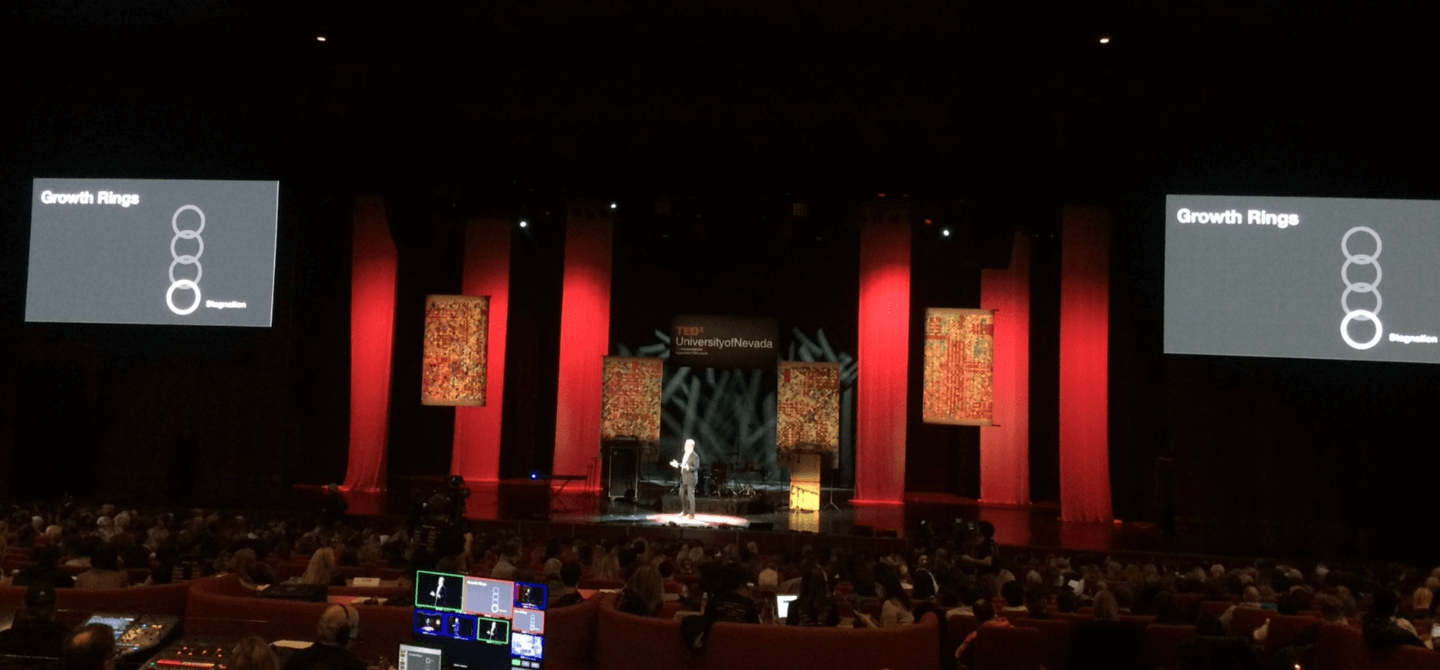

This scenario isn’t hard for anyone to imagine, and it doesn’t just affect work – it can happen at home, in schools, on athletic teams, and more. Why don’t people step up and say what they are thinking when they have good ideas to contribute? Why can’t they say, “Boss, I’m not sure about this idea, and here’s why?”

Psychological Safety is a term first coined by Amy Edmonson as she conducted groundbreaking research on teams and interactions among teammates. She defined psychological safety as the “perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks in the workplace” (Edmonson, 1999).

While studying this concept in hospitals, Edmonson found that the hospitals with the HIGHEST number of reported mistakes also had the fewest avoidable deaths. Her research concluded that when team members felt safe to admit mistakes and challenge each other in decisions, it produced a culture in which less life-threatening mistakes occurred.

Let’s think about this again: The place where they reported the most mistakes was ACTUALLY the safest hospital.

How can we learn from mistakes if we don’t point them out and name them? We teach children to learn from mistakes (or we say that phrase to them at least), but we struggle to carry that ethos into adulthood. Most people in the workplace tend to not report mistakes for fear of being looked at unfavorably by their peers or in job performance evaluations. But how can anyone be creative with ideas if they don’t have psychological safety?

“Studies of creativity suggest that the biggest single variable of whether or not employees will be creative is whether they perceive they have permission to speak.” —David Hills

Does Psychological Safety Mean Being Nice?

They’re not synonymous terms, but it all depends on your definition of “nice.” I would consider it nice to let me know that a plan I’ve created may have some critical holes in it. But if a leader has not created psychological safety, niceness can be misconstrued as “going with the flow” or “not objecting.”

So what is psychological safety? It’s expressing your full self while not fearing repercussions, and it’s a way to hold teammates accountable to agreed-upon terms. For example, if the leadership team agreed to receive feedback from frontline employees two times per week, a high degree of psychological safety would allow someone to say, in front of the boss, “We agreed upon this but are not following through.” Teams simply cannot operate most effectively without psychological safety as an operational norm.

Stages of Psychological Safety

Psychological safety is about the central leader relinquishing power to the team. Matthew Barzun, in The Power of Giving Away Power, said, “Encourage leaders to allow all members of the team to share their views and study the problem from many angles, with each person bringing their knowledge. This becomes power with instead of power over.”

To have a power with mentality, the leader must create psychological safety. Dr. Timothy Clark identified the four stages we progress through before we feel comfortable challenging the status quo:

- Stage 1 — Inclusion Safety: You are safe to belong to the group. You are comfortable being yourself and your strengths are accepted by the group. Inclusion safety satisfies the basic human need to connect and belong.

- Stage 2 — Learner Safety: You are challenged by the group to learn, and you are also allowed to challenge group members to learn and grow. This stage comes with asking questions and giving feedback while others ask you questions and give you feedback. Learner safety satisfies the need to learn and grow.

- Stage 3 — Contributor Safety: You are a meaningful contributor to the team, and members of the team want you to contribute your strengths. It is believed that the team would not be as strong without you being a strong contributor.

- Stage 4 — Challenger Safety: You are allowed to challenge the status quo. This could be anything from a commonly used system in the organization all the way to the purpose or vision of the organization.

Conclusion

Psychological Safety is a simple concept, yet it can be difficult to cultivate. Everyone wants to be heard, and we want our strengths to be recognized and sought after when building a team. As a leader, ask yourself if you are consistently creating a forum for feedback by listening to the ideas of others. While it’s fine to disagree, it’s not okay to simply brush off others without hearing them. Doing so sends the message to all observers that pushing back, having creative thoughts, or asking questions is not acceptable on your team. How will you make psychological safety the first priority of your team?

“Negative environments kill thousands of great ideas every minute. Creative environments become like greenhouse, where great ideas get seeded, sprout up, and flourish.” —John C. Maxwell